- 2017-2018 — As the first Director of Vocational Services for suburban Philadelphia disability services nonprofit The Arc Alliance, I opted to launch services with PA Office of Vocational Rehabilitation’s new (as of 2016) PETS (Pre-Employment Transition Services) program for high school special education programs for which I designed the two PETS-specific workplace readiness training programs. Both were approved for OVR-funded PETS workplace readiness and self-advocacy training respectively.

2009-2014 — Founder and part-time CEO of SymBionyx, the for-profit successor to the SymBionyx Foundation, and a remote disability services platform technology start-up created to commercialize the output of the Messiah College Collaboratory WERCware project team (see following) through the development of its first commercial Tymer app product, and its pilot project deployment with Goodwill Industries Keystone Region and recruitment and hand-off of day-to-day management to a full time professional manager CEO and CIO based out of offices in suburban D.C.

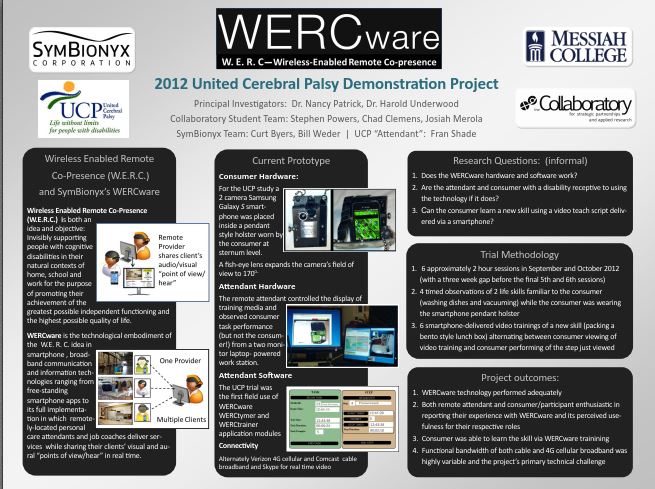

2007-2014: Leadership of Messiah College College Collaboratory for Strategic Partnerships and Applied Research WERCware project. In response to my clients with autism’s post high school challenges in first employment I invented Wireless-Enabled Remote Co-presence (W.E.R.C.)–embodied in WERCware®, embodied in products and services as WERCware–to enable remote job coaching support of people with autism and other cognitive disabilities. I founded the SymBionyx Foundation to partnered with a Messiah College’s Collaboratory student team and faculty from the engineering, computer science and education departments to develop a succession of WERCware technologies. Initial development and proof of concept projects with the Capital Area Intermediate Unit and United Cerebral Palsy of Central PA were funded by thee grants from PA state agencies totaling $65K.

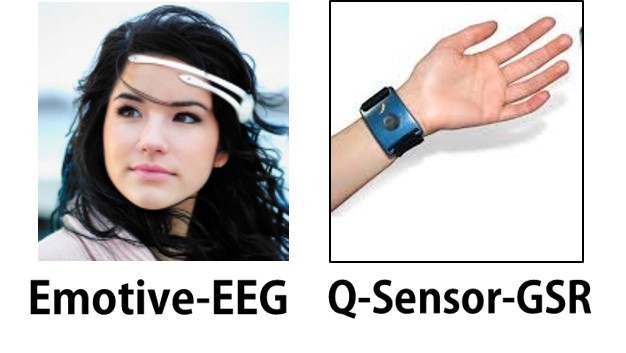

The final Collaboratory WERCware project resulted from my observation that mothers of my clients with autism were detecting impending “meltdowns” in rising stress in their child’s voice. I proposed development of an artificial neural network (ANN)-based smartphone app that could. 1) recognize rising stress and an impending “meltdown” in a user’s voice, 2) correlate voice data with input from a wearable biometric monitor and, 3) trigger an alert, automated intervention script, or summon assistance as per defined escalation criteria. The final WERCware team successfully trained an ANN to 85% effectiveness in recognizing voice stress and were developing interface software for both the Affectiva Q-Sensor (for galvanic skin response) and Emotive’s wearable EEG reader in the final year of the project.

2001-2003: As an independent consultant I researched, created and packaged a wireless broadband company concept for aggregating a leading independent wireless broadband provider in each of 20-30 mid-size markets into an integrated network that is then pre-configured for a roll-up acquisition of each provider in a single transaction. That concept became JetStream Broadband, an Orlando, Florida-based commercial wireless broadband and Internet Service Provider when I “sold” a majority interest in the company concept to recruit its funder/CEO, create value for my minority position and secure my own employment as its VP of Business Development.

1996-1999: I became the 8th hire and a Director of Business Development for Evangelical market-targeted Web portal Crosswalk.com only after management agreed to change from a subscription business model to one based on top-of-web page advertising that came to be called “banner ads”– with which business model Crosswalk raised $90 million in its 1997 IPO—ticker symbol AMEN. I transferred from business development to content production to become founding channel producer and editor of a new Spiritual Life Channel. I later added running Crosswalk’s volunteer chat monitor program to my editorial portfolio and for which I designed its training program and hired and managed the chat program’s only full time employee.

1997: Lead consultant and project manager for a team of academic consultant specialists conducting an analysis and making recommen-dations for a cooperative model online learning platform for the Coalition of Christian Colleges and Universities, a trade association of 92 Christian colleges and universities. Christian University Globalnet was launched in 1998.

My team’s report and recommendations as presented to representatives of 32 of the CCCU’s 92 member institutions. I opened the consultation with an initial overview and high level summary presentation on the project.

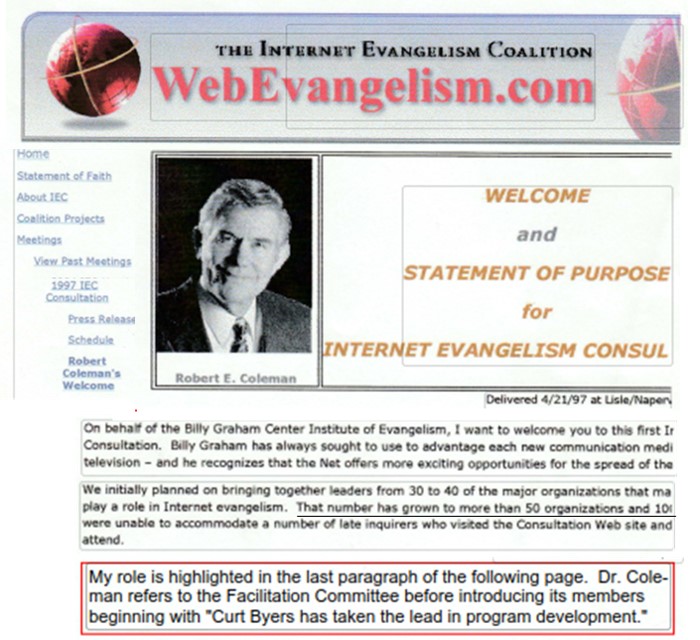

1996-1997: Planning coordination consultant for the first international Internet Evangelism Consultation, sponsored by the Billy Graham Center’s Institute of Evangelism

I was retained by project management contractor Christianity Today Inc. to be the sole paid planning committee member for the nine months leading up to the first international Internet Evangelism Consultation, sponsored by the Billy Graham Center at Wheaton College. The primary purpose of the Consultation was to both educate and assess, over the course of three days, the perceived need for and interest in creating an ongoing internet evangelism organization–in effect, a trade association–and if affirmed, secure the endorsement of its creation by consultation attendees and election of charter officers. For this and other reasons, participating organizations were required to send either a CEO or COO/EVP along with their senior internet operations staffer. Every invited major player organization attended. I delivered one of the opening plenary addresses. Consultation attendees strongly affirmed the founding of the Internet Evangelism Coalition.

1996: I wrote Life With God: First Steps, with Helen Johns, as part 1 of a four part Life With God introductory curriculum on the Christian faith and membership in The Brethren in Christ Church, for the BIC publishing arm, Evangel Press. The project was offered to me after Evangel Press’ editors’ review of the UK Live Program material. First Steps is effectively a complete rewrite and adaptation into conventional print format (i.e. prose vs. image-centric) of LIVE Program’s approach and core concepts for the U.S. market.

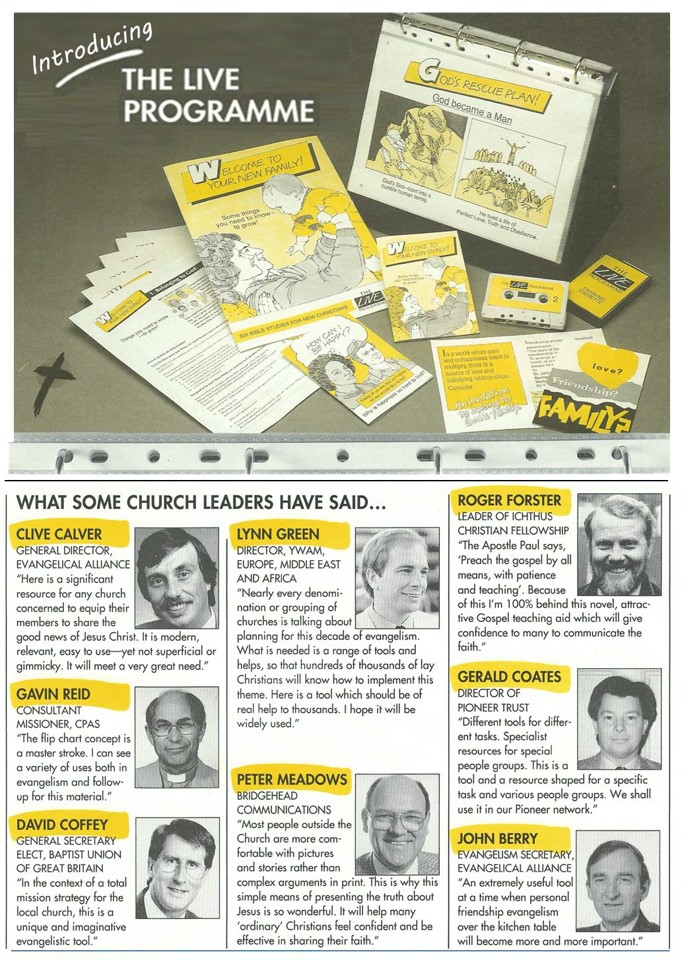

1992: UK publication of the LIVE Programme, by a leading UK church media publisher. The LIVE Programme was the first comprehensive, multiple media format, family metaphor-based introduction to Christianity curriculum and local church outreach program in the UK. It was, for its time, unique in its featuring of non-white ethnicities in a highly visual presentation format chosen for an urban target demographic for whom English was likely a second language. I proposed and secured the endorsements of eight of the U.K.’s highest profile U.K. evangelical church leaders in the bottom half of the promotional piece below.)